…and counting!

You may already know, 2019 is the International Year of the Periodic Table, an initiative by the IUPAC with support from the UNESCO. It commemorates 1869, the year Dmitry Mendeleev published his formulation of the Periodic Law and subsequently proposed the Periodic System. Legend has it that such a discovery came to him in a dream; a more realistic account would be that he worked with cards trying to find a suitable arrangement for the elements, finally visualizing the trends we are all now familiar with.

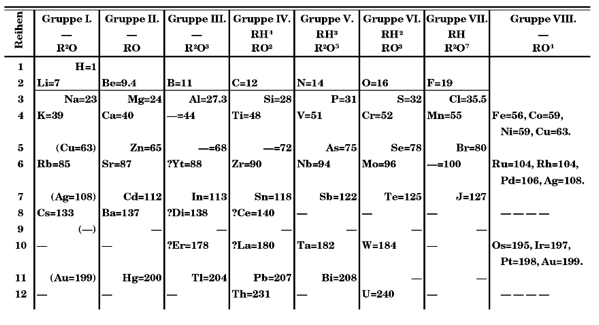

Mendeleev’s periodic table (version of 1971).

Mendeleev’s was obviously not the first attempt to classify and group chemical elements in series, but his Periodic System is closely related to the table we use today, hence the fame. What’s more, the same scheme was independently developed by Julius Lothar Meyer and published a year after Mendelev’s report. Lothar Meyer had previously proposed a smaller version with only 28 elements arranged by valence; five years later, Mendeleev published his table with all the elements known to that date (63) arranged by atomic weight. Mendeleev’s pioneering decision was to leave space for the unknown, that is, he predicted the existence of undiscovered elements, being later proved right by the discovery of gallium or germanium, among others. Moreover, he was able to accurately estimate the physico-chemical properties of those elements!

Trends in elemental properties had been observed as early as 1789, when Antoine Lavoisier classified what he considered “chemical elements” into gases, metals, nonmetals, and earths in his famous Elementary Treatise on Chemistry. Almost 40 years later, Döbereiner proposed that certain elements could be grouped in triads based on their chemical properties (for example, Li–Na–K). Curiously enough, the properties of the second element of each triad could be roughly estimated from those of the first and third elements, giving rise to the Law of Triads. Many other chemists were also able to identify trends in relatively small groups of elements, but a scheme encompassing them all was still lacking.

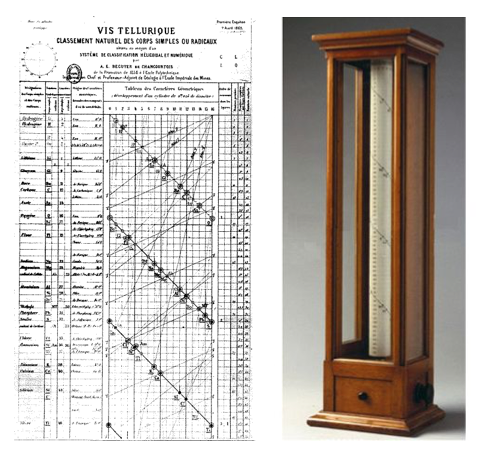

In 1862, the French geologist Alexandre-Émile Béguyer de Chancourtois devised an early form of the periodic table called the telluric helix (as tellurium was located at its center). His was a fully functioning three-dimensional classification, where the elements where arranged by their atomic weight in a spiral around a cylinder. He noticed periodicity, that is, elements with similar properties would appear at regular intervals. However, his table had little success, probably because its construction was considered too complex at the time.

Another unsung hero in this story is John Newlands. He noticed that, when elements were placed by increasing atomic weight, similar physical and chemical properties recurred at intervals of seven (note that the noble gases had not been discovered yet, hence Newlands’ periodicity of seven instead of eight). This Law of Octaves, which he compared to the octaves of music, was vastly criticized by his peers and his contribution was only acknowledged many years later. One of his critics, William Odling, developed himself a table very similar to that of Mendeleev’s, even superior in some aspects. However, he also failed to get proper credit. Finally, although Gustavus Hinrichs stated his ideas on periodicity as early as 1855, his eccentric personality obscured the recognition of his role in the development of periodic laws.

Mendeleev’s arrangement based on atomic weight finally became the current periodic table based on atomic number thanks to Henry Moseley, who was able to determine the atomic number of the elements by bombarding them with x-rays and analyzing the wavelength of the emitted radiation.

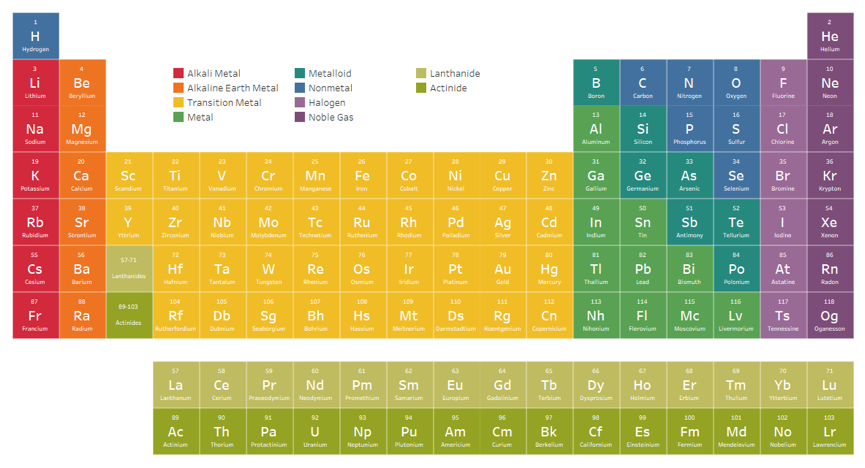

It is clear now that the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements is one of the greatest achievements in modern science. It has proven to be much more than a table, it is a common language to chemists, physicists and biologists, to name a few. We use it every day, in the very same way a musician uses a pentagram or mathematicians have their own language. Moreover, it is a tool that allows us to predict certain behaviors of elements (that is, their physico-chemical properties).

The fact that we still use such a periodic system today evidences the huge accomplishment of all these (and many more) scientists that pushed forward the frontiers of chemistry almost two centuries ago.

As an anecdote, while Mendeleev got an element named after him (element 101: mendelevium), Lothar Meyer’s contributions gained him a mineral. You guessed it: the lotharmeyerite.